The Real Constraint on Data Centers in Space

GPUs are already flying in orbit. The physics works. The economics are getting there. But there is one problem that could kill the whole idea.

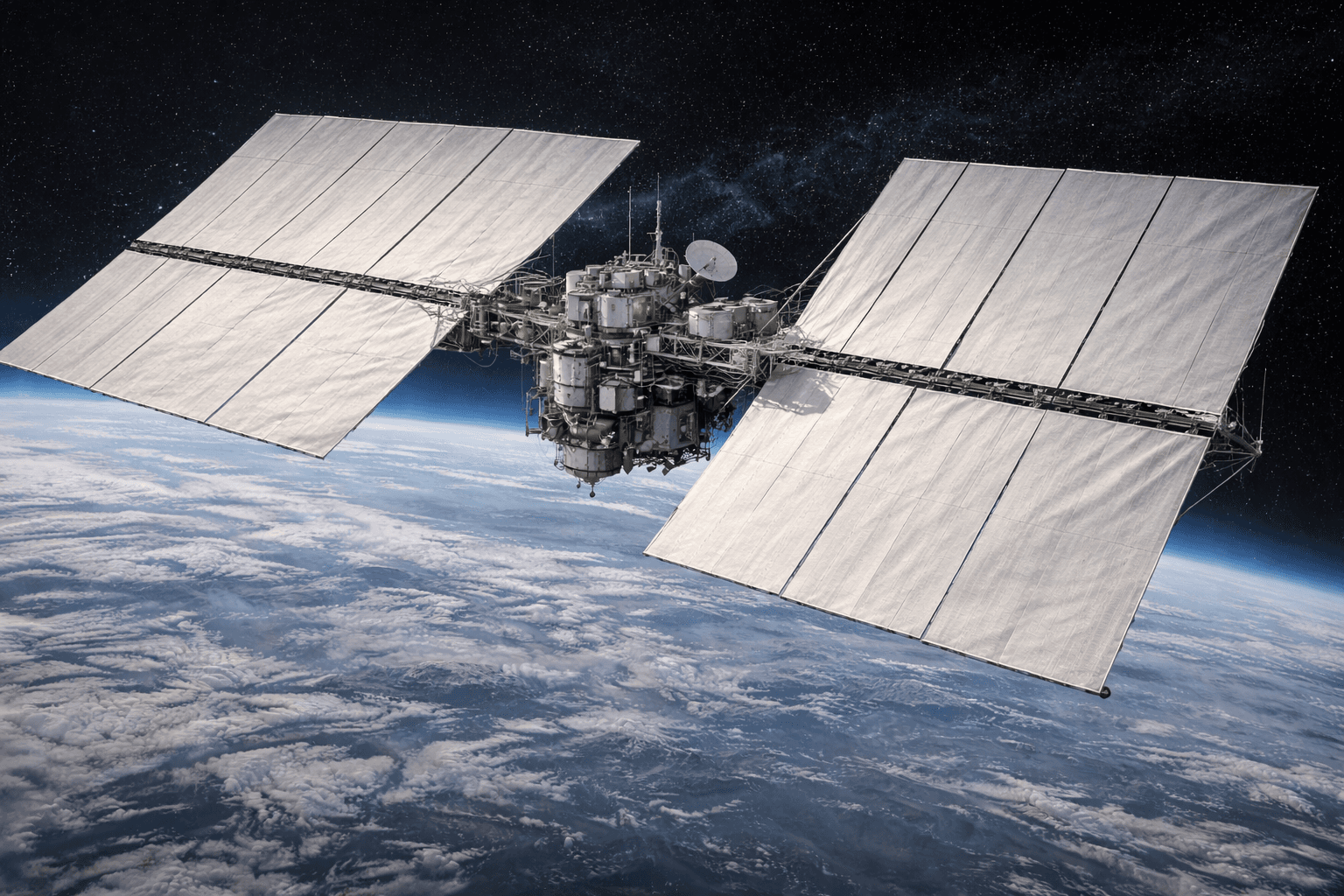

A rendering of the Starcloud-1 satellite, which successfully carried the first NVIDIA H100 GPU into orbit in November 2025 to test space-based AI computing.

The Year It Stopped Being Crazy

Every few years, someone proposes putting data centers in space. The idea gets a few headlines, engineers point out why it will not work, and everyone moves on. This time is different.

In November 2025, a startup called Starcloud launched a 60kg satellite carrying an Nvidia H100 GPU into orbit. They trained an AI model on Shakespeare's complete works while circling Earth at 350 kilometers. It worked. That was the first time a state-of-the-art data center GPU operated in space.

A few weeks later, Google announced Project Suncatcher: TPU chips launching into orbit by 2027, with a long-term vision of 81-satellite clusters forming orbital AI compute grids. Not a research project. A product roadmap.

Jeff Bezos told an audience at Italian Tech Week that gigawatt data centers in space would beat the cost of terrestrial data centers within 10 to 20 years. Elon Musk said SpaceX would simply scale up Starlink V3 satellites to make it happen. Eric Schmidt acquired Relativity Space and confirmed the purchase was specifically to build orbital data centers.

Three of the richest people on Earth, plus Google, all betting on the same idea in the same year. Some of these are speculative visions, some are concrete product roadmaps -but the convergence itself is the signal. If even half of these plans materialize, we are looking at a fundamental shift in how AI infrastructure gets built.

But most analysis of orbital compute misses the central question.

In orbit, cooling is hard. Power is abundant. Latency is unavoidable. Density keeps rising. But none of these kill the idea. The real killer is simpler: you cannot fix anything.

Why Smart People Keep Coming Back to This Idea

Before getting to the hard problems, it is worth understanding why orbital compute keeps attracting serious people. The advantages are not hypothetical. They are physics.

Start with power.

Above the atmosphere, the sun delivers about 1,361 watts per square meter. No clouds. No weather. In a dawn-dusk sun-synchronous orbit at 650 kilometers, satellites see sunlight more than 95% of the time. A solar panel in space can generate roughly 8 times more energy than the same panel on a rooftop in Arizona. Generation is abundant -though batteries and power conditioning units add mass penalties that partially offset this advantage.

This matters because power is the binding constraint on AI infrastructure right now. Utilities are telling hyperscalers to come back in 2028. Permitting new data centers near population centers takes years. Eric Schmidt testified to Congress that data centers could need an additional 67 gigawatts by 2030. His argument: harvesting solar energy directly in space might be the only way to meet that demand.

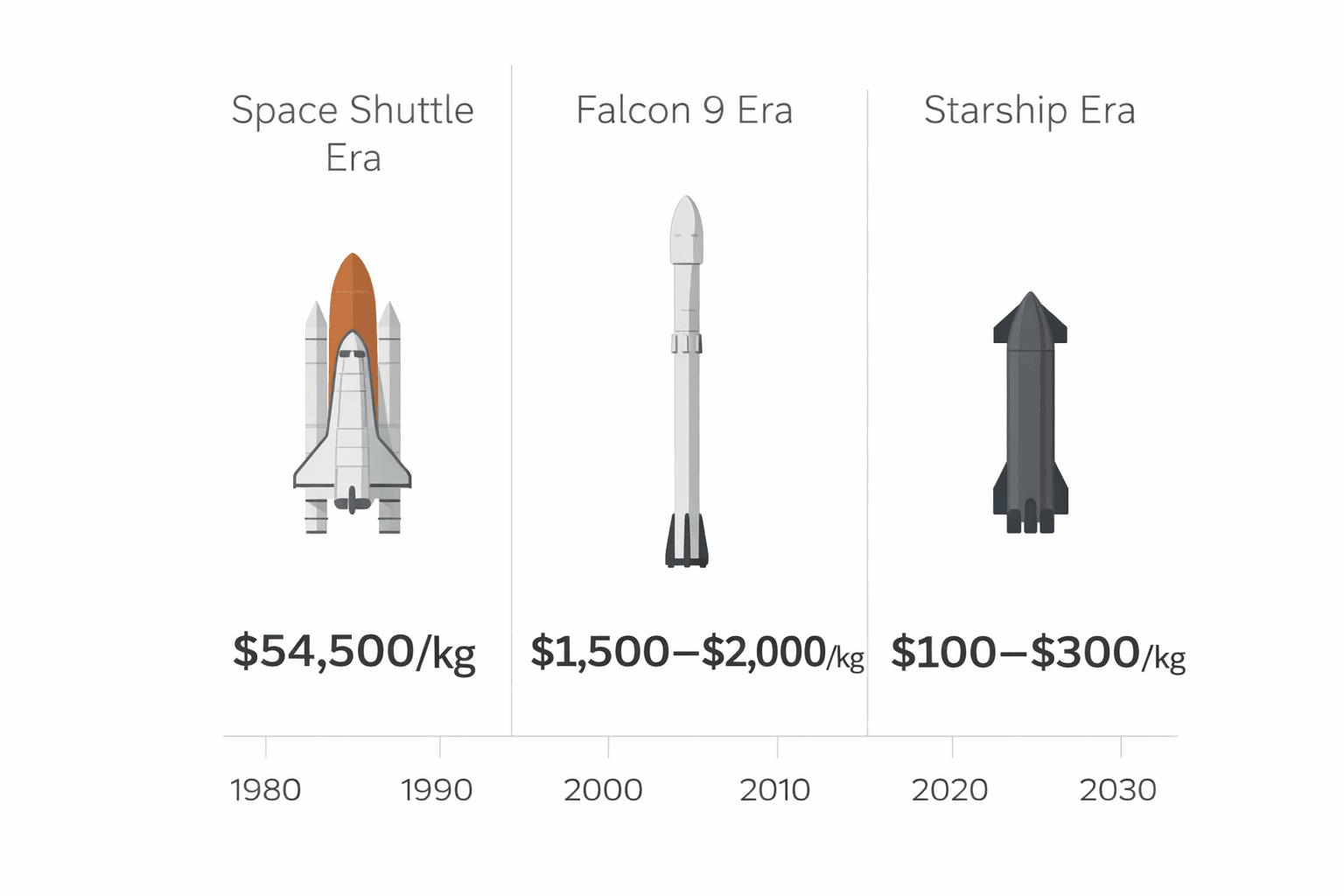

Launch costs have collapsed.

| Launch Vehicle | Cost per kg to LEO | Era |

|---|---|---|

| Space Shuttle | $54,500 | 1981-2011 |

| Falcon 9 (reusable) | $1,500-2,000 | 2017-present |

| Starship (projected) | $100-300 | 2026-2030 |

Google's analysis suggests that at $200 per kilogram, launch costs amortized over a satellite's lifetime roughly equal the energy costs of running equivalent compute on Earth. That is the inflection point where “free solar” starts to matter economically.

Radiation survivability is improving -but survivability is not the same as long-term reliability.

Google tested their TPU v6 chips in a proton beam simulating five years of low Earth orbit radiation. The chips survived up to three times the expected dose without hard failures. High-bandwidth memory showed some errors beyond certain thresholds, but for many workloads these are manageable with error correction. The old assumption that you need expensive radiation-hardened processors for everything in space is becoming outdated.

But radiation risk is often understated. The danger is not just sudden failures from cosmic ray hits. Radiation causes gradual analog degradation that is much harder to model: transistor threshold shifts, SRAM bit flips, PLL instability, timing skew. Over years, these effects accumulate. Training stability degrades. Long-running jobs become unreliable. ECC overhead increases. This is not a solved problem -it just becomes another argument for why prediction and monitoring are everything.

Permitting is simpler.

There are no NIMBY battles in orbit. No municipal zoning hearings. No water rights disputes. No grid interconnection queues. You need FCC and FAA approval, but you skip the years of local permitting that can delay terrestrial projects.

The Thermos Problem

If the goal is abundant cooling and avoiding land constraints, why not just put data centers in the ocean? Microsoft tried this with Project Natick: underwater servers had one-eighth the failure rate of land-based servers. But ocean data centers still required hauling modules to the surface for repairs. With orbital data centers, repair is essentially impossible. That distinction matters more than almost anything else -and it starts with a physics problem most people misunderstand.

Ask most people how hard it is to cool things in space, and they will say: not hard, space is cold. This is completely wrong. Space is not cold. Space is a vacuum -and a vacuum is an insulator, not a cooler. Think of a thermos: it keeps your coffee hot precisely because the vacuum prevents heat transfer. Your orbital data center is inside a giant thermos.

On Earth, you blow air over hot components, run water through heat exchangers, use evaporative cooling towers. None of these work in a vacuum. The only way to reject heat in space is thermal radiation: pointing large panels at cold deep space and letting them emit infrared energy.

The physics of radiative cooling follows the Stefan–Boltzmann law, which describes how much heat an object radiates as a function of its temperature: a blackbody (an idealized surface that radiates heat as efficiently as physics allows) at 45 degrees Celsius radiates about 520 watts per square meter, while one at 15 degrees radiates about 390. But these theoretical numbers depend heavily on operating temperature and radiator efficiency. In practice, after accounting for non-ideal emissivity, view factor losses, panel geometry, dust degradation, shadowing, and thermal control margins, usable heat rejection is often closer to 100 to 350 watts per square meter. This creates enormous area requirements:

| IT Load | Radiator Area Needed | Roughly Equivalent To |

|---|---|---|

| 10 kW (small edge node) | 30-100 square meters | Studio apartment |

| 1 MW (GPU cluster) | 3,000-10,000 sq meters | Soccer field |

| 100 MW (mid-size DC) | 300,000-1M sq meters | 30-100 football fields |

| 1 GW (hyperscale) | 3-10 square kilometers | Small town |

To put this in perspective: the International Space Station rejects about 75 to 90 kilowatts with roughly 2,500 square meters of radiator area. That is the entire station's heat load, including life support for six astronauts. A single high-density AI rack on Earth can hit 50 kilowatts by itself.

These radiators are not just large. They are fragile, heavy, and present massive targets for space debris. They must handle extreme thermal cycling: minus 100 degrees Celsius in shadow, then plus 120 degrees when the sun hits them. Every 90 minutes. For years.

The cooling problem is solvable, but it dominates the design. When you see renderings of orbital data centers, most of what you are looking at is thermal management. An orbital data center is not a server room in space. It is a power plant that happens to do some computing.

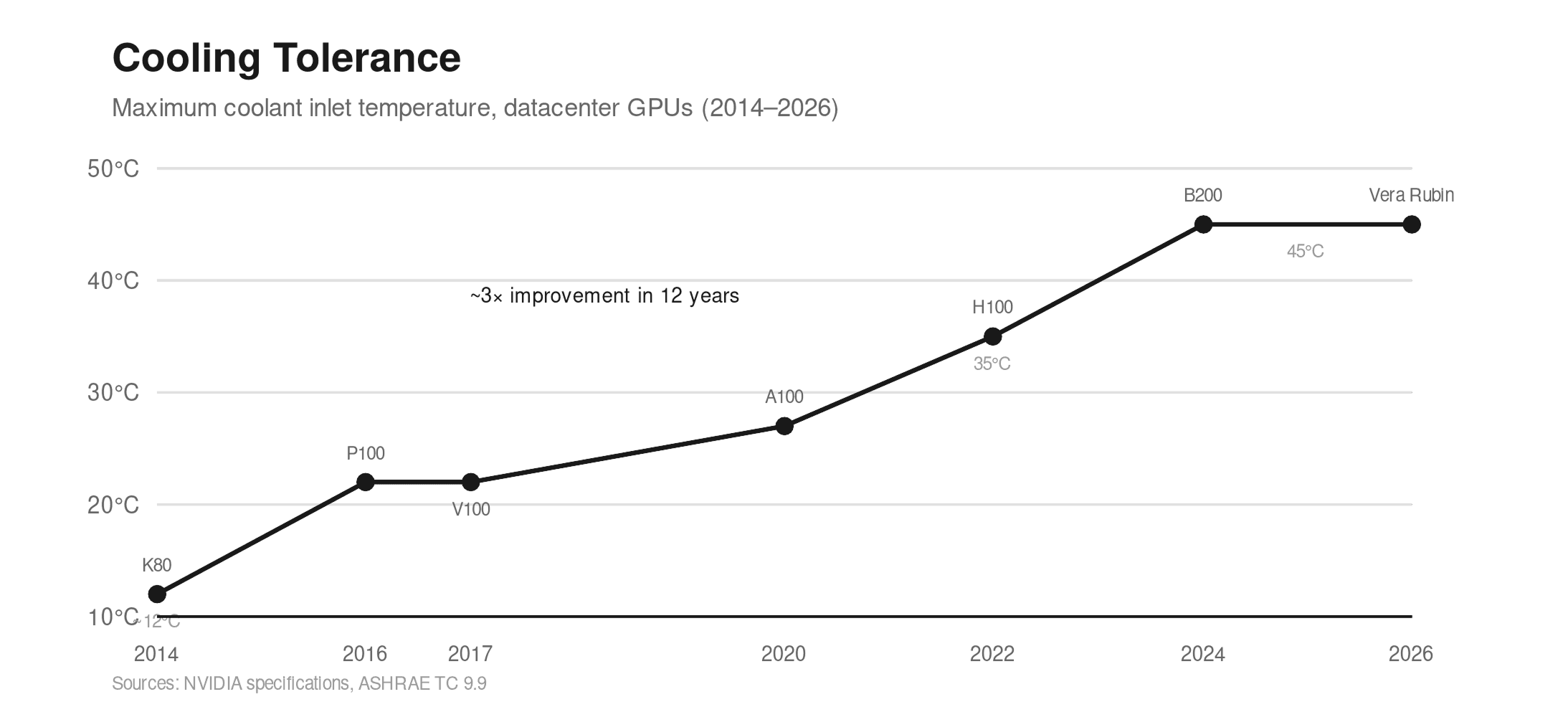

But here is something worth watching: the cooling problem is becoming more tractable per unit area, even as absolute power continues to rise.

Radiative cooling efficiency depends heavily on temperature. The Stefan-Boltzmann law says heat radiated scales with the fourth power of temperature. A radiator at 45 degrees Celsius rejects roughly 3 to 4 times more heat per square meter than one at 15 degrees.

And here is the trend that changes everything: datacenter GPUs from both Nvidia and AMD are increasingly tolerant of warmer cooling. The shift over the past decade is dramatic:

| GPU | Vendor | Year | TDP | Max Coolant Inlet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tesla K80 | NVIDIA | 2014 | 300W | 10-15°C |

| FirePro S9150 | AMD | 2014 | 235W | 15-20°C |

| Tesla P100 | NVIDIA | 2016 | 250W | 18-27°C |

| Tesla V100 | NVIDIA | 2017 | 300W | 20-25°C |

| A100 | NVIDIA | 2020 | 400W | 25-30°C |

| Instinct MI250X | AMD | 2021 | 560W | 30-35°C |

| H100 | NVIDIA | 2022 | 700W | 35°C |

| Instinct MI300X | AMD | 2023 | 750W | 32-45°C |

| Blackwell B200 | NVIDIA | 2024 | 1000W | 45°C |

| Vera Rubin | NVIDIA | 2026 | ~1500-1800W | 45°C |

In 2014, the Tesla K80 required coolant temperatures below 15°C to avoid throttling. In 2026, the Vera Rubin platform runs efficiently with 45°C coolant -a three-fold increase in thermal tolerance in just over a decade. As Jensen Huang announced at CES, this shift means no water chillers are necessary; the system can be cooled using warm water and standard dry coolers, even in hot climates.

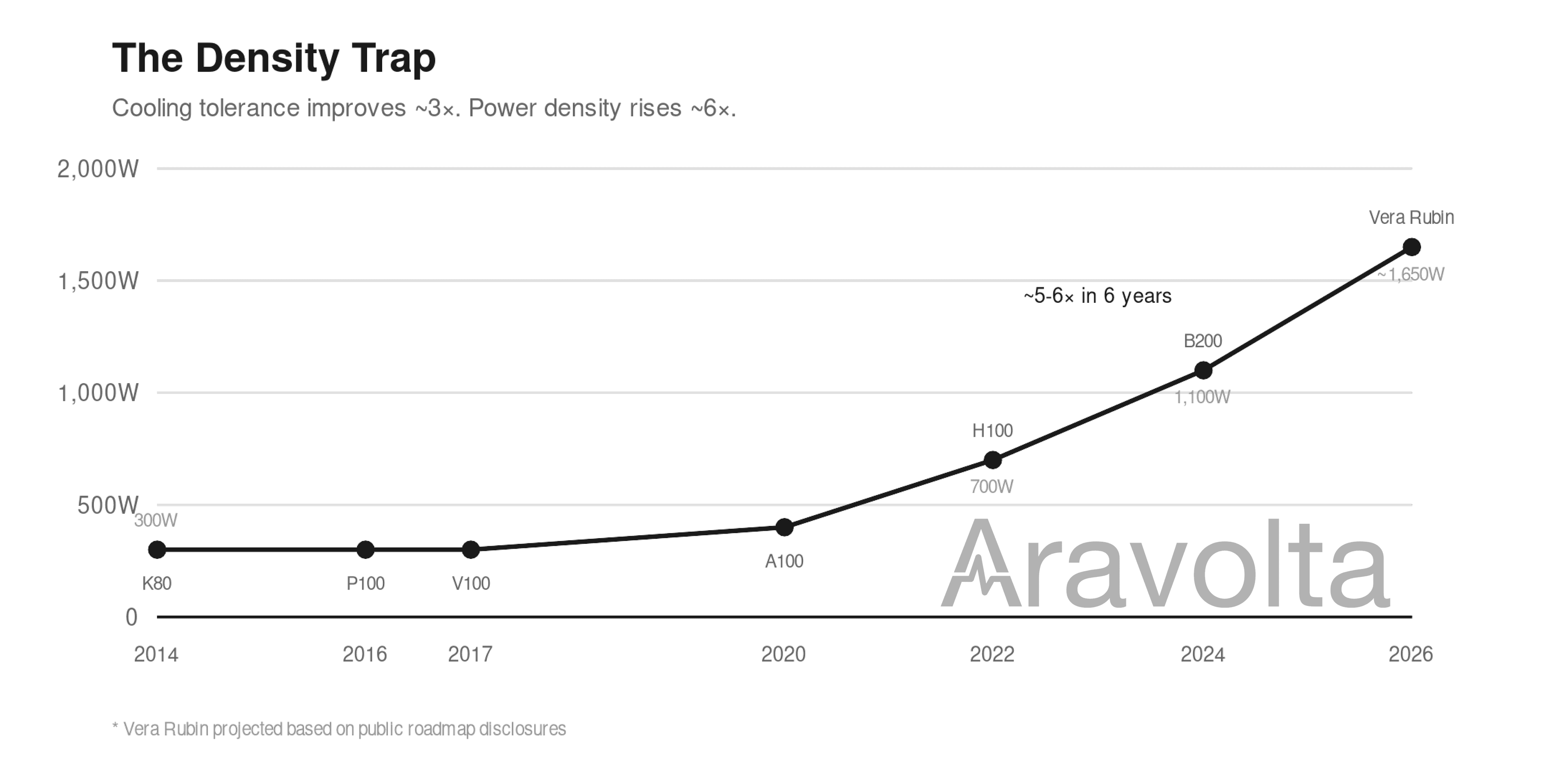

The Density Trap

But there is a countervailing force that threatens to undo all of this progress: power density is exploding even faster than cooling tolerance is improving.

Look at how TDP has grown across the same GPU generations:

| GPU | Year | TDP | Change from Previous Gen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tesla K80 | 2014 | 300W | - |

| Tesla P100 | 2016 | 300W | Flat |

| Tesla V100 | 2017 | 300W | Flat |

| A100 | 2020 | 400W | +33% |

| H100 | 2022 | 700W | +75% |

| B200 | 2024 | 1000-1200W | +43-71% |

| Vera Rubin | 2026 | ~1500-1800W | +50-80% |

From 2014 to 2020, TDP was essentially flat at 300-400 watts. Then it doubled to 700 watts with H100, doubled again to over 1000 watts with Blackwell, and is projected to approach 1500-1800 watts with Vera Rubin based on density trends. In six years, power per chip increased roughly 5-6 times.

Rack density tells the same story. Traditional CPU racks ran at 10 to 15 kilowatts. Today's H100 racks hit 50 to 70 kilowatts. The GB200 NVL72 reaches 132 kilowatts per rack. NVIDIA's roadmap shows 240 kilowatts per rack coming soon, with 1 megawatt rack designs already unveiled at OCP 2025.

Performance per watt is improving, but every efficiency gain gets immediately reinvested into more compute, not lower power. Terrestrial data center economics reward density -customers want more compute per rack, more revenue per square foot. Vendors respond by cramming more compute into the same footprint. AI model scaling makes this worse: bigger models mean more parameters, more tokens, more layers. Even if chips got twice as efficient, models grow four times larger, and net power density still increases.

This matters more in space than on Earth. On Earth, high power density is annoying but solvable -build bigger chillers, add more cooling, run thicker cables. Space externalizes none of these costs. Every watt must be generated, stored, transported, and rejected locally. Space does not care about your FLOPs per watt. It cares about watts per kilogram. Watts per square meter. And all of those are getting worse.

This is the tension at the heart of orbital compute: temperature tolerance is improving by 3x, making radiators more efficient per square meter. But power density is increasing by 6x, meaning you need to radiate far more total heat. The net effect: cooling remains the dominant engineering challenge. The radiator area you launch is the radiator area you have. You cannot add more later.

But space has one advantage Earth does not: abundant power generation. Solar in orbit generates 5 to 10 times more energy per panel than on Earth. If you can solve the thermal problem, generation capacity stops being the binding constraint. The question is not how many FLOPs you can do per watt. It is how many watts you can afford per kilogram.

The likely outcome is not megascale orbital hyperscalers with kilometer-wide radiator farms. It is sparse, low-density, highly distributed clusters optimized around thermal constraints rather than compute density. Many small nodes, each with modest power budgets, connected into constellations that can be incrementally replaced as individual satellites fail or become obsolete.

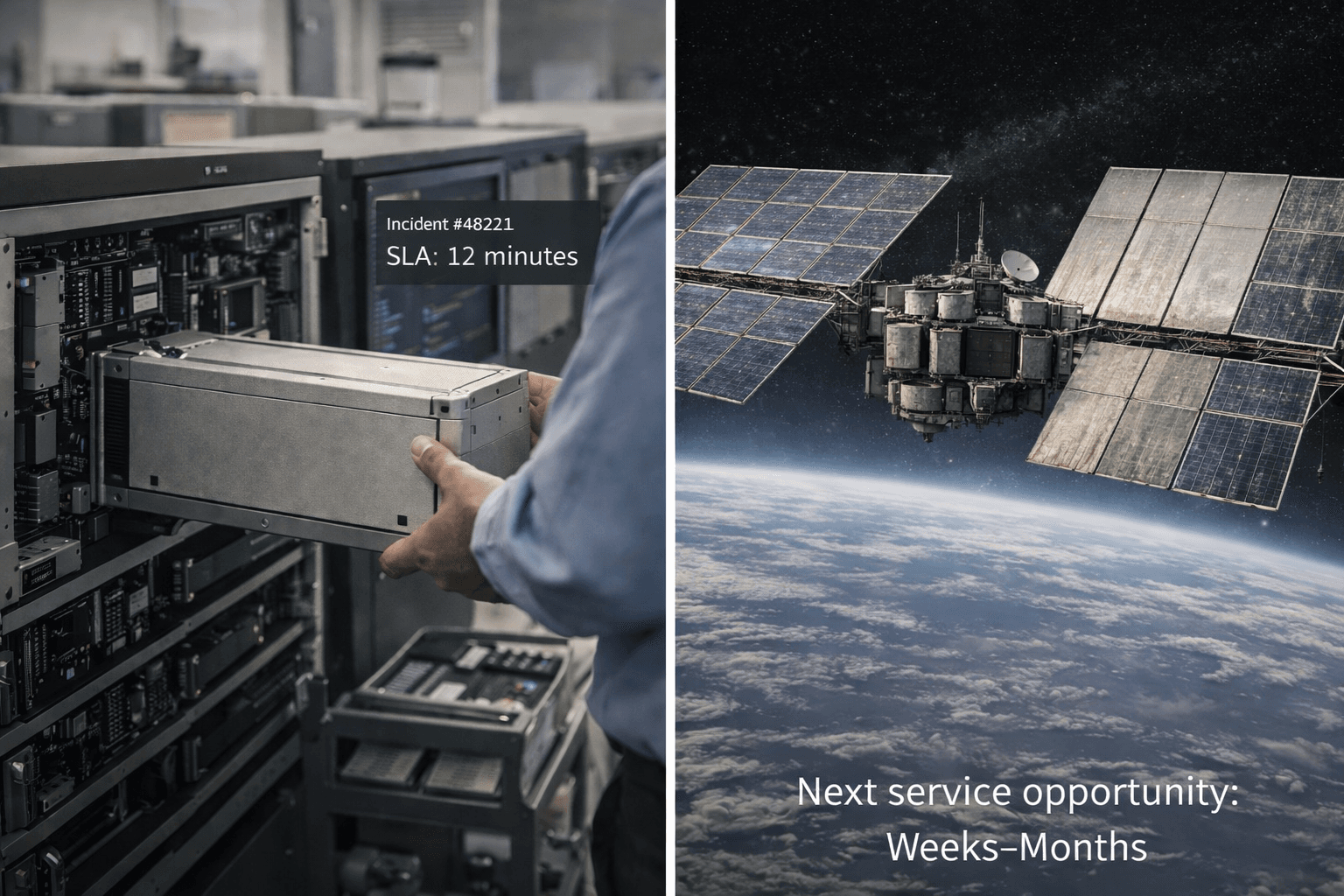

The Problem Nobody Is Solving

Now we arrive at the issue that underlies everything else: maintenance. On Earth, when a server fails, you swap it. When a cooling pump breaks, a technician fixes it. None of this works in orbit.

Two distinct constraints are often conflated. Repairability: when hardware fails, it cannot be fixed. Upgradability: when hardware becomes obsolete, it cannot be swapped. On Earth, you do both routinely. In orbit, you do neither. Each constraint independently destroys traditional data center economics.

Starcloud-1, the satellite with the H100 GPU, has an expected operational lifetime of 11 months. Then it deorbits and burns up. Google explicitly acknowledges this in their Suncatcher paper: since you cannot replace failed TPUs in space, the simplest solution is redundant provisioning -launch spare capacity and hope you do not need it all.

This creates cascading problems: shorter asset life (3-5 years versus 5-7 terrestrial), frozen technology that cannot be upgraded, binary failure modes, and debris risk that creates correlated failures across entire constellations.

And it is not just hardware. In orbit, software bugs are just as fatal: bad firmware, control plane errors, scheduling bugs, security breaches, faulty update rollouts. On Earth, you can SSH in and restart a hung process. In orbit, if the watchdog timer fails, you have a very expensive paperweight. The constraint is not just that you cannot fix hardware -you cannot fix errors.

When You Cannot Repair, Prediction Becomes Everything

In terrestrial data centers, you can afford to be somewhat reactive. Something breaks, you fix it. The cost of a failed drive is the cost of a new drive plus a few hours of technician time.

In orbital systems, reactive maintenance does not exist. The only strategy is predictive: identify problems before they become failures, and design systems to tolerate the failures you cannot prevent.

This changes the value proposition of telemetry completely.

On Earth, hardware monitoring is useful but optional. Many operators run minimal telemetry and just replace things when they break. The economics work fine.

In space, hardware monitoring is existential. You need to know:

- Which components are showing early signs of degradation

- How much margin remains before thermal limits are breached

- Whether radiation is accumulating faster than expected

- When to migrate workloads away from failing hardware before it dies

- How to schedule replacement satellites before capacity drops below acceptable levels

This is not incremental improvement over terrestrial monitoring. It is a fundamentally different operating model where prediction accuracy directly determines whether the business works at all.

We see a version of this with terrestrial GPUs. Identical hardware can have radically different lifespans depending on workload, thermals, and utilization patterns. A GPU running steady inference at 65% utilization ages very differently than one spiking to 100% for training runs every afternoon. The difference can be years of useful life.

Orbital compute amplifies this dynamic. Every satellite will need granular, real-time health monitoring. The operators who build the best predictive systems will have the lowest effective costs. The ones who fly blind will have satellites dying unexpectedly and taking their investment with them.

The good news: we are getting dramatically better at this.

Modern telemetry systems can track hundreds of parameters per chip in real time. But the real breakthrough is in multi-asset learning: understanding how entire systems behave together, not just individual components. A GPU does not fail in isolation. It fails because of how cooling loops interact with power delivery, how thermal cycling stresses particular board layouts, how workload patterns create cascading wear across interconnected subsystems.

The companies building these models on terrestrial data center fleets are accumulating something invaluable: the ability to predict failures weeks or months in advance by understanding the relationships between upstream infrastructure and downstream assets. At Aravolta, this is exactly the problem we work on every day. The same capabilities that help lenders understand GPU depreciation curves and operators maximize asset life translate directly to orbital applications, just with existentially higher stakes.

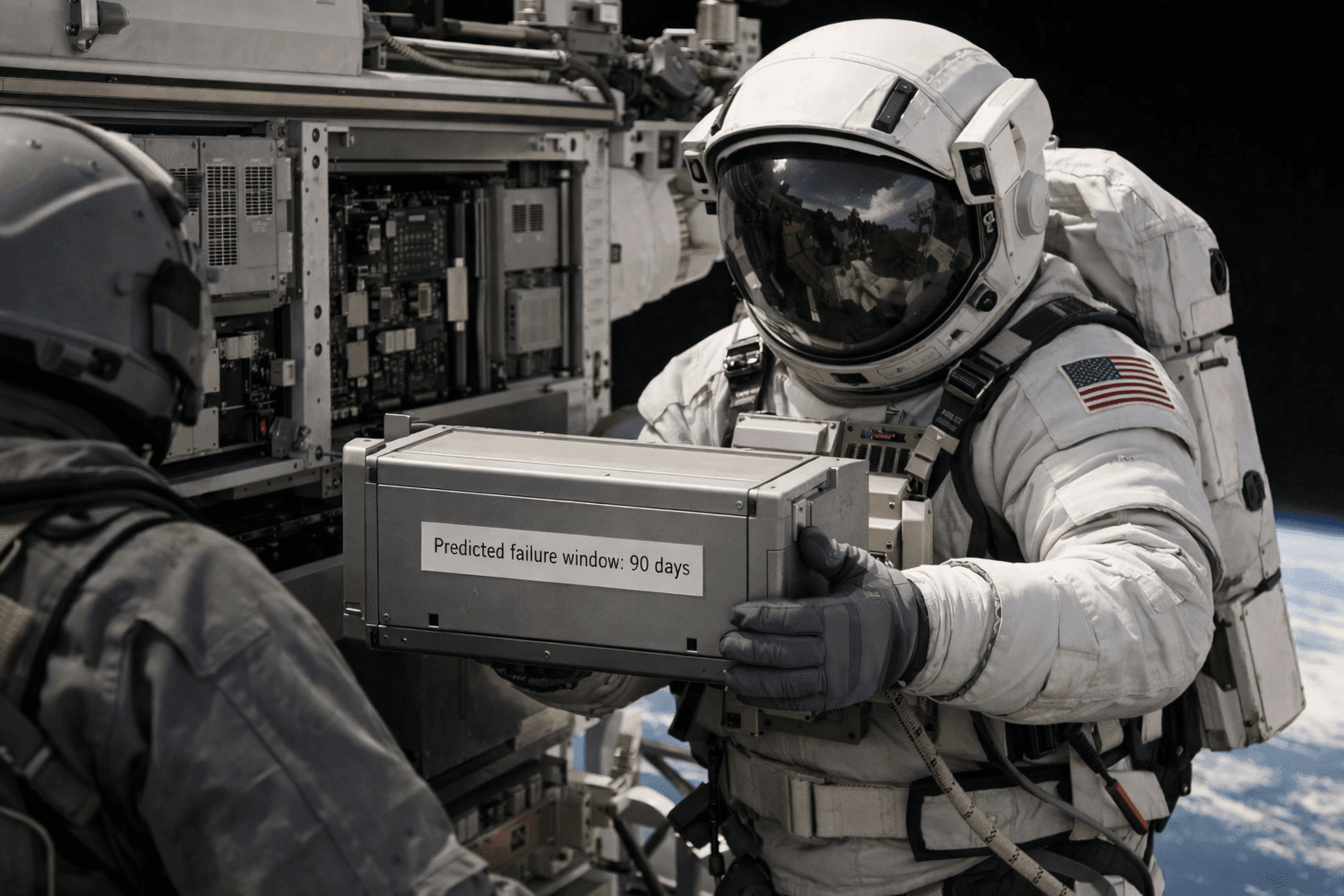

And here is the speculative part: what if prediction gets good enough that repair becomes economically viable?

Right now, the assumption is that orbital hardware is disposable. But if you can predict with high confidence that a specific cooling pump will fail in 90 days, suddenly the economics of a repair mission start to look different. SpaceX is already working on crewed Starship. Blue Origin is developing commercial space stations. The cost of putting a technician in orbit is falling alongside everything else.

Imagine a future where orbital data centers are designed with modular, swappable components, and a specialized repair crew visits quarterly to replace the parts that telemetry flagged months earlier. It sounds like science fiction, but so did reusable rockets fifteen years ago. But here is the key point: even if repair becomes possible, it only works if prediction is nearly perfect. You cannot send a technician to fix something you did not know was breaking. The constraint shifts from “repair is impossible” to “prediction must be extraordinarily good” -which reinforces, rather than undermines, the central argument.

What To Watch

If you are evaluating orbital compute as an investor, operator, or potential customer, here are the signals that matter:

Starship economics. Nearly every positive business case for orbital compute assumes SpaceX hits something close to their cost targets. If Starship achieves $200 per kilogram, the economics shift dramatically. If it stalls at $1,000 per kilogram, orbital compute remains an expensive niche. Track SpaceX's progress closely.

Thermal system reliability. The radiator and cooling loop design is where projects will succeed or fail. Anyone can buy solar panels. Rejecting megawatts of heat through radiation while surviving thermal cycling and micrometeorite impacts is hard engineering. Watch for how long demonstration missions actually operate versus their design life.

Constellation versus monolithic architecture. Google's Suncatcher approach uses clusters of many small satellites that can be replaced incrementally. Starcloud's vision involves larger individual platforms. The distributed approach has better failure characteristics and upgrade paths. The monolithic approach might be more thermally efficient. The winning architecture is not yet clear.

Predictive maintenance capabilities. The operators who build the best telemetry and prediction systems will have the lowest costs. Look for companies that treat monitoring as a core competency rather than an afterthought. Tracking actual workload intensity and thermal stress rather than assuming averages becomes absolutely essential when repair is impossible.

Demonstration mission longevity. Starcloud-1 is designed for 11 months. Google's initial satellites launch in 2027. How long these actually operate in good health will tell us more than any whitepaper about what the real depreciation curve looks like.

So Where Does This Leave Us?

Orbital data centers are real. Hardware is flying. The physics works. The economics are getting closer every year.

But the central challenge is not power, not cooling, not radiation, not launch costs. It is the impossibility of repair. Every other constraint can be engineered around with enough money and clever design. The no-repair constraint cannot be. It changes the entire operating model: shorter asset lives, higher redundancy requirements, frozen technology, binary failure modes.

The latency constraint is structural: low Earth orbit adds 20-40 milliseconds round-trip, geostationary adds 600 milliseconds. There is no engineering solution -it is the speed of light. Add Doppler shifts from satellites moving at 7.5 km/s, handover jitter between satellites, and variable routing delays, and latency-sensitive inference becomes economically uncompetitive. Orbital compute will be for training and batch processing, not answering questions in real time.

It is not just a latency problem -it is a data gravity problem. Moving petabytes of terrestrial data to orbit is inefficient. Compute must move to where the data is generated.

Where it makes sense: processing data already in space (Earth observation, avoiding the cost of downlink), defense applications (compute physically inaccessible to adversaries), batch AI training that tolerates latency, and regulatory arbitrage when terrestrial infrastructure is blocked. Where it does not: general-purpose cloud, real-time inference, anything requiring consistent low latency or frequent hardware refresh.

This means predictive maintenance becomes the critical capability.

Not a nice-to-have -the thing that determines whether the business works. The operators who can predict failures before they happen will have viable businesses. The ones who cannot will have expensive satellite graveyards.

Stay Updated

Get the latest insights on AI infrastructure, GPU management, and data center operations delivered to your inbox.

No spam, unsubscribe anytime.

Sources & Citations

- Starcloud-1 H100 GPU satellite launch - NVIDIA Blog (Nov 2025)

- Google Project Suncatcher technical paper - Google Research (Nov 2025)

- Bezos remarks on space data centers - Italian Tech Week via InsideHPC (Oct 2025)

- Musk statement on Starlink V3 scaling - NotebookCheck (Oct 2025)

- Eric Schmidt acquires Relativity Space - Interesting Engineering (May 2025)

- Microsoft Project Natick underwater data center - Microsoft Research

- ISS Active Thermal Control System Overview - NASA

- Starship launch cost projections - NextBigFuture

- Space-based solar power economics - Scientific American

- Blue Origin Blue Ring spacecraft - SpaceNews

- NVIDIA Vera Rubin 45°C cooling announcement - ACHR News (Jan 2025)

- ASHRAE liquid cooling standards W1-W5 - ASHRAE TC 9.9

- NVIDIA DGX B200 datacenter specifications - NVIDIA

- NVIDIA Blackwell B200 1200W TDP specifications - Wccftech (Mar 2024)

- GB200 NVL72 132kW rack density - Introl (OCP 2025)

- Data center rack density trends 2016-2025 - Enconnex / AFCOM State of the Data Center Report

- GenAI power consumption and datacenter infrastructure - Deloitte TMT Predictions 2025

- Cost of space launches to low Earth orbit - CSIS Aerospace Security Project (2022)